Vitaly

The letters are unfamiliar, the vowels are not visible, everything is reversed. But it's not so bad! We explain how to understand the alphabet, vowel sounds, and learn to read confidently.

Imagine: you open a book in Hebrew and try to read the first sentence. The letters look strange, there are no vowels... You ask in surprise: how do you read Hebrew? Which way round? Get used to it: you really do need to read from right to left! For a beginner, reading a text in Hebrew seems like an almost impossible task, don't you agree? However, it's not as daunting as it seems — you can learn if you understand the basic principles.

In this article, we will cover the basics of reading Hebrew: we will learn the alphabet (consonants and vowel signs), discuss the pronunciation of sounds, transcription rules, consider some exceptions and peculiarities of writing, practise reading text without vowel signs based on context, and list typical mistakes made by beginners. Let's make one thing clear from the outset: we will be talking about reading printed text. Written Hebrew — cursive letters and handwriting — will be left out of the discussion, as that is a separate topic.

Beginners often ask: how is the Hebrew alphabet read? It consists of 22 letters, and almost all of them represent consonant sounds. There are no capital letters in Hebrew – all letters are written in the same style. Reading proceeds from right to left.

Each letter has its own name (alef, bet, gimel, etc.), but the text must be read according to the sounds. As a rule, the pronunciation of a letter coincides with the first sound of its name. For example, the letter ב is called «bet» and is read as the sound [b] (or [v] – more on that later), ל is called «lamed» and gives the sound [l], מ – «mem» sounds like [m], and so on.

But where are the vowels? Instead of separate letters for vowel sounds, Hebrew uses a system of special symbols called vowel points («nikud» in Hebrew). These are dots and lines that are placed under, above, or inside consonant letters to indicate the vowel sound that follows that letter. For example, a single dot at the bottom left indicates the sound [i], a combination of three dots under the letter indicates the sound [e], a line under the letter indicates the sound [a], a dot inside the letter ו indicates the sound [o], and ו itself without a dot is usually read as [u] or [v].

There are 17 vowels in total, and learning them is part of the basic language course. In textbooks for beginners, children's books and texts from the Tanakh (Bible), vowels are usually marked, making such texts easier to read – you see a complete «syllable» consisting of a consonant and a vowel and immediately understand what sound to pronounce.

Example of vowels in Hebrew

How are Hebrew letters with vowels read? It's very simple: first pronounce the consonant, then immediately pronounce the vowel that this vowel signifies. For example, מָ is written as the letter mem with a line under it (vowel kamatz), read together as [ma]. Gradually, you will get used to it and begin to perceive the combination of letter + vowel as a single whole.

The rules of pronunciation in Hebrew are quite simple, but there are a few things worth knowing. First, all sounds are pronounced clearly and fully, regardless of their position in the word. Unlike in English, vowels in Hebrew are not «swallowed» in unstressed syllables — every a, o, e and i sounds as distinct as if it were stressed. For example, the words lomed (לומד – «studying») and kotev (כותב – «writing») should be pronounced with clear consonants [d] and [v] at the end – without softening them to [t] or [f]. If you say kotef instead of kotev, you will get a completely different word (by the way, kotef – קוטף – means «to pick (fruit)»). Therefore, make sure that the last letter of the word sounds as it should, and not as the English ear is accustomed to.

Secondly, Hebrew doesn’t have the concept of soft and hard consonants as we understand them. All consonants sound approximately «hard» (they are not softened before i or e, as is the case in Russian). For example, the name Leah (לאה) is pronounced in Hebrew as [le-a], without softening the l – not [lya]. The letter lamed always sounds like a hard [l], regardless of the following vowels. Similarly, there is no Russian contrast between [с]-[сь] or [н]-[нь] — in Hebrew, these sounds are the same.

Thirdly, there are several specific sounds that take some getting used to. The letter ר (resh) in Israeli pronunciation resembles a lisped [r] – the sound is formed in the throat, similar to the French R. Don't worry if you can't get it right away: many people speak with the familiar Russian [r], and they are understood. The letters ח and כ (without a dot) produce the sound [x], similar to the Ukrainian г or the sharply pronounced х in Russian (as in the word «бах»). The sound h (letter ה), on the other hand, is soft and exhaled, without a wheeze — it is closer to the light English h in home. Russian speakers often do not distinguish it, substituting it with either [х] or [г], but try to catch the difference.

Fourth, keep in mind that there are two letters in the alphabet that do not produce a sound on their own: א (alef) and ע (ayin). Don't be alarmed when you see them in a word — they are usually either not pronounced at all or only separate neighbouring vowel sounds. Simply put, if you see א or ע in a word, you just read the vowel sound that follows that letter (and you can mentally skip the «silent» letter itself).

The stress in most Hebrew words falls on the last syllable. This is not a strict rule (there are many exceptions), but as a general guideline when reading a new word, remember: most likely, the last vowel will be stressed. For example, délét (דלת – «door») is correctly pronounced with the stress on the e (délét), and Yerevan (ירוון – the name of the city) with the stress on the last a. Over time, as you expand your vocabulary, you will know where the stress is placed in each specific word, but at the initial stage this is a typical stumbling block – don’t hesitate to ask native speakers or check in a dictionary.

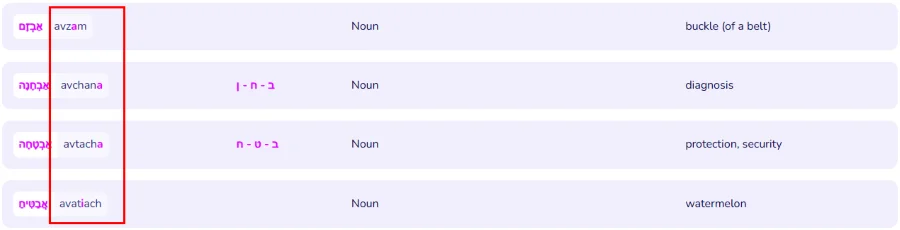

The capital letter is highlighted in a different colour

What should you do if you are not yet confident in your reading skills? Transcription comes to the rescue – recording the pronunciation of Hebrew words using the Russian or Latin alphabet.

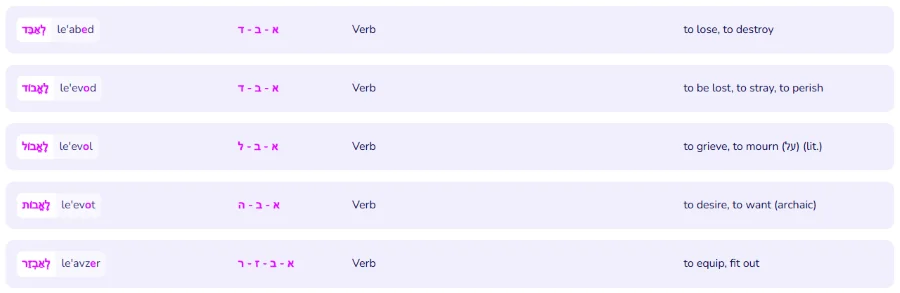

Transcription of Hebrew words into Latin letters

Virtually all textbooks and dictionaries for beginners provide new words in transcription. This is really helpful at first: when you see, say, «shalom» next to the word שלום, you will immediately understand how to read it.

However, transcription has its drawbacks. First, it doesn’t provide a complete representation of the sound: for example, the soft guttural sound ה is often rendered with the Russian letter «г», and students then mistakenly pronounce it as [г]. Or, for example, some textbooks transcribe the letter ח as х, while others transcribe it as ch; as a result, readers get confused about where the sound [х] is and where something else is. Secondly, when you get used to transcription, it is easy to become dependent on it and never learn the letters themselves. But knowledge of the alphabet and independent reading skills are absolutely essential for progress in the language.

What should you do? Use the transcription as an aid, but nothing more. If it makes you feel more comfortable, write down a few words in Russian letters, but look at the original at the same time. Try to switch to reading Hebrew letters as soon as possible — first with vowels, and then without. A good technique is to read a new word using the transcription, then cover it up and try to read the same word on your own. The sooner you «let go» of the transcription, the sooner you will start reading for real.

Every language has its nuances, and Hebrew is no exception. Here are a few features that are important to keep in mind when reading.

Some letters are pronounced differently in different situations. For example, the letter Bet (ב) with a dot (dagesh) is pronounced [b], and without a dot – [v]. Similarly, Kaf (כ) with a dot is pronounced [k], and without a dot – [x]; Pe (פ) with a dot is pronounced [p], without a dot – [f]. The letter Shin (ש) with a dot on the top right conveys the sound [sh], and if the dot is on the top left (such a letter is called Sin), it is pronounced [s]. These dots are only used in texts with vowel marks; in normal writing, you have to distinguish between, say, [b] and [v] based on your knowledge of the word. Fortunately, there are not many such pairs, and you will soon remember them.

Five letters of the alphabet have a special form when they appear at the end of a word (so-called «final» forms). These are the same letters, but they are written differently: ך (final kaf), ם (final mem), ן (final nun), ף (final pei), ץ (final tsadi). When reading, recognise them by their general shape and position — for example, any long «hook» extending below the line at the end of a word is most likely a final nun or pei (and not a random squiggle).

Another characteristic feature is abbreviations. In books, newspapers, and even messages, you will encounter abbreviated words and phrases — a few letters with an apostrophe or quotation marks. The question arises: are abbreviations in Hebrew read letter by letter or as a complete word? There is no universal rule here: it all depends on the specific abbreviation. Usually, an abbreviation is read as if it were written in full, simply knowing what the combination of letters means. For example, the abbreviation ד״ר (dalet–quotation marks–resh) means doctor, and when read, it is pronounced «doctor». However, the combination ת״א is deciphered as Tel Aviv (the name of the city) and is read as «Tel Aviv». If you are unsure how a particular abbreviation is pronounced, it is best to check a dictionary or ask a native speaker. Over time, the most common abbreviations will become familiar.

Important: do not confuse these abbreviations with sound symbols. The same symbol ׳ (apostrophe) can be placed next to a letter to indicate a special pronunciation – for example, ג׳ is read as [dzh] (like the English J). But this is a separate topic, a subtlety that you will learn as you delve deeper into the language.

One of the main challenges for students is to transition from educational texts with vowel markings to regular texts without them. Adult Israelis do not use vowel markings when writing at all: newspapers, books, websites — everything is printed with ‘bare’ letters. How do they read words correctly?

Context and knowledge of the language come to the rescue here. Over time, you will begin to automatically recognise familiar words by their letter combinations. Many words contain the letters ו and י, which act as vowels (matres lectionis): for example, י often indicates the sound [i], and ו indicates [o] or [u]. This provides clues in the words – at least some vowels are visible. In addition, the form of the word usually suggests what the pronunciation should be: native speakers know that כתב is most likely read as katav (he wrote), and ספר as sefer (book), because other options do not fit the meaning.

It is best to start reading texts without vowel marks gradually. First, try reading familiar words and short phrases: you will be surprised, but you will recognise familiar words even without vowel marks. Then move on to sentences: try to understand the general meaning and figure out unfamiliar combinations of letters from the context. For example, if the sentence is about the days of the week and you come across the combination שבת, it is most likely Shabbat (Saturday) and not something else — simply because other words with these letters would not fit here.

Context is your best friend when reading without vowels. This is how every Israeli reads: they see a skeleton of consonants in front of them and fill in the missing vowels in their mind, relying on the meaning. At first, it seems like magic, but with practice, you will master this skill. Just take your time and give your brain time to get used to the new way of reading.

In conclusion, let us list a few typical mistakes that beginners make when reading Hebrew:

Reading Hebrew is a skill that can be mastered with patience. At first, the letters seem like incomprehensible symbols, but step by step, you begin to see the sounds and words behind them. The alphabet is fairly quick to learn, the reading rules are logical and concise, and then it's all about practice. Read a little every day — even just a couple of lines — and very soon you will find yourself reading Hebrew texts with ease.