Vitaly

Both languages are Semitic and related, but knowing Hebrew will not help you understand Arabic. This article discusses the similarities in roots, writing and grammar, as well as the key differences that make them two completely different worlds.

Is Hebrew similar to Arabic? This question often arises among those interested in Middle Eastern languages. Hebrew and Arabic are ancient Semitic languages with a common origin, so there are indeed certain similarities between them. However, upon closer examination, it becomes clear that there are also significant differences between them.

Hebrew and Arabic belong to the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Both originated from a common ancient proto-language of the region, so they can be called related. Historically, Hebrew belongs to the group of Canaanite (North-West Semitic) languages spoken in the ancient Levant, while Arabic belongs to the Central Semitic languages of the Arabian Peninsula. They diverged thousands of years ago, developing in different directions. Interestingly, modern Hebrew was actually revived from ancient Hebrew at the end of the 19th century, while Arabic never ceased to be used, evolving from classical Arabic (the language of the Koran) to modern dialects.

Both languages are written from right to left and use a consonantal alphabet (abjad) of Semitic origin, inherited from Phoenician writing. For clarity, here is a common greeting in each language.

Both phrases mean «peace be with you» – we see a common wish for peace and even a similar root in the words ש-ל-ו-ם / س-ل-ا-م (SLM), conveying the idea of well-being.

Although these two languages developed independently for a very long time, they share a number of common features due to their common origin.

Hebrew and Arabic have inherited many cognate words from their Proto-Semitic ancestor. For example, the word for «house» sounds similar: in Hebrew it is בית (bayit), and in Arabic it is بيت (bayt). Both come from the same ancient root B-Y-T.

Similar parallels can be found in other basic concepts: the Hebrew word «shalom» (peace) corresponds to the Arabic «salam», «ben» (son) to the Arabic «ibn», demonstrating the similarity of vocabulary.

Both languages use consonants as the basis for words and do not write short vowels. Writing is done from right to left, which may be unusual for speakers of European languages.

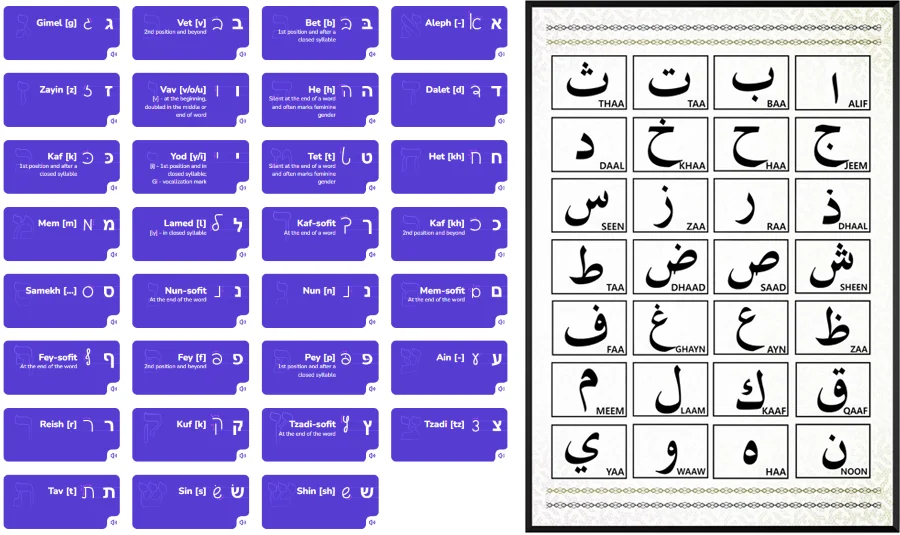

There are 22 letters in Hebrew and 28 in Arabic, but the principles are similar: letters mainly denote consonant sounds, and additional symbols (nikud in Hebrew, harakat in Arabic) are used for vowels when necessary. Interestingly, the names of many letters are also similar: for example, the Hebrew «alef» corresponds to the Arabic «alif», and «bet» corresponds to the Arabic «ba», which indicates the common origin of the alphabets.

In both languages, nouns and adjectives have gender – masculine or feminine. For example, the word «teacher» will have different genders for men and women (Hebrew more – teacher, mora – teacher; Arabic muʿallim – teacher, muʿallima – teacher).

Another characteristic feature of both languages is that adjectives usually follow nouns and agree with them. For example, «big house»: in Hebrew, bayt gadol, in Arabic, bayt kabir – in both cases, the order is «house big».

Both languages use a system of adding endings or affixes to connect words: for example, prepositions are often attached to words (Hebrew ב–, Arabic ب– mean «in, inside»), and possessive suffixes allow you to say «my/your house» in one word.

Hebrew and Arabic construct words according to a similar principle: from a set of several (usually three) consonants – the root – many words are formed with the help of different vowels and additional sounds. This principle is unique to Semitic languages. For example, the root K-T-B in Arabic gives the words «kataba» (he wrote), «kitab» (book), and the similar root K-T-B in Hebrew gives the words «katav» (he wrote), «ktav» (handwriting) and «sefer» (book, through historical sound changes). Knowing the root makes it easier to guess the meaning of words with the same root: for example, in both languages, the root S-L-M is associated with peace and well-being (shalom, salaam – peace; shalem – whole, Islam – literally «surrendering oneself to peace/God»). This common approach to word formation brings Hebrew and Arabic closer together and distinguishes them in many ways from Indo-European languages.

Given these similarities, a logical question arises: if the languages have so much in common, why can't a native Hebrew speaker understand Arabic (and vice versa) without special training? The fact is that there are even more differences between the languages.

Despite their common Semitic roots, the differences between Hebrew and Arabic are much more noticeable. The languages developed separately, and today, native speakers of Hebrew and Arabic cannot understand each other without training. Let's look at the key differences.

Visually and technically, the writing systems of the two languages differ.

The Arabic alphabet connects letters within a word: the writing is cursive, and each letter has a different shape at the beginning, middle, and end of a word. For example, the Arabic letter م (mim) is written differently in a word, connecting with neighbouring letters. In Hebrew, however, letters are not connected to each other — each is written separately (even cursive handwritten variants retain the separation of letters). This makes reading Hebrew more «legible» visually for a beginner, whereas Arabic script is perceived as a single pattern.

In addition, the set of letters themselves differs: Hebrew has 22 basic letters (plus 5 of them have a separate final form), while Arabic has 28 letters. Although historically both alphabets grew out of Phoenician, the modern appearance of the letters is completely different. It is easier for beginners to learn Hebrew letters, as they are more graphically distinct, whereas in Arabic many letters differ only in dots and require getting used to.

Comparison of letter writing: on the right is the Arabic alphabet, on the left is the Hebrew alphabet

Phonetically, Arabic and Hebrew sound very different.

Modern Hebrew has lost many ancient sounds and simplified its pronunciation. For example, guttural and emphatic consonants that were present in Biblical Hebrew (such as ע, ח, ק, ט, צ) are now pronounced more simply or coincide with other sounds. In Israeli Hebrew, most speakers do not distinguish between the sounds [ħ] and [h] (the words עם [ʕ] and אמ [ʔ] sound the same), the letters ק and כ are pronounced as the usual [к] or [х], and the letter ט is indistinguishable from т.

Arabic, on the other hand, has retained a rich set of ancient sounds. Speakers of Hebrew are unfamiliar with Arabic phonemes such as ع (ayn – a deep guttural sound), ح (ha – a sharp aspirated sound), ق (qaf – a hard «k» deep in the throat), ص, ض, ط, ظ (so-called emphatic consonants, which are particularly articulated). Arabic also has sounds such as th (مثل ث), dh (هذا ذ) and others that do not exist in Hebrew. As a result, Arabic sounds «deeper» and harder to Israelis, with an abundance of guttural sounds, while Hebrew sounds softer and more «hissing» to Arabs.

The stress in words also differs: in Hebrew, it is almost always on the last syllable, while in classical Arabic, it is more often on the penultimate or third-to-last syllable. All this creates a noticeable contrast in the sound of the two languages.

Cases: in literary Arabic, there are three cases for nouns (nominative, genitive, accusative), which are expressed by different vowel endings (-u, -a, -i) or nunation. For example, the word «kitab» («book») can sound like kitabu, kitab, kitabi in different functions. In Hebrew, there are no case endings at all — the word «sefer» («book») will be sefer in any role, and connections are expressed by prepositions or word order.

Dual number: Arabic retains the grammatical form of the dual number for most nouns (e.g., «kitaban» – «two books») and even conjugates verbs with a dual subject. In Hebrew, however, the dual form has been retained only for a few words (mainly paired concepts such as «eyes» – einayim, «ears» – oznayim), and usually the numeral shtayin (two) plus the usual plural form is used to refer to two objects.

Plural: In addition to regular endings, Arabic has many so-called «irregular» plural forms that must be memorised (e.g. kitab – books kutub). In Hebrew, the vast majority of nouns form the plural simply by adding a suffix (-im for masculine, -ot for feminine: sefer – sfarim, book – books).

Verb forms: In Arabic, there are traditionally 10 basic types (forms) of verbs, while in Hebrew there are 7 basic binyan forms. In Arabic, verbs are conjugated according to person and number, with different endings and prefixes, and the form of the verb also depends on the voice and mood (indicative, subjunctive, imperative). In Hebrew, conjugation also changes according to person/number, but there are no variable endings for voice – there are no moods as such (the imperative is formed from the future tense), and the verb form is usually the same for all contexts. For example, in Arabic, verbs in the past and future tenses have completely different bases, while in Hebrew, the past, present and future are constructed more regularly from a single root using predictable patterns.

All these nuances make Arabic grammar more difficult to learn: you have to remember more exceptions and rules of agreement. Hebrew, especially in its modern form, has become simpler: there are no cases, no verb conjugations, and fewer word forms. This is one of the reasons why people often say that Hebrew is easier to learn than Arabic.

Another important difference is the degree to which the language is fragmented into dialects.

The Arabic language is a whole family of diverse dialects and colloquial variants. Egyptians, Moroccans and Syrians each speak their own variant of Arabic, which can differ greatly – sometimes no less than Russian and Polish. To facilitate communication between speakers from different countries, there is literary Arabic (fusha), a unified written standard based on the classical language. However, in everyday life, Arabs from different countries often have difficulty understanding each other without switching to Fusha. It turns out that the single name «Arabic» covers a multitude of linguistic variations.

Hebrew is much more uniform in this regard. There are different sociolects and accents (for example, the speech of immigrants from different countries – «Russian» Hebrew, «Moroccan» Hebrew, etc.), but essentially it is one standardised modern Hebrew, which all Israelis speak and write. There is no separate spoken and literary language – the language of newspapers, books and television is the same as that spoken on the street, with minimal stylistic differences. The absence of strong dialectal differences simplifies learning: you master one language and can communicate with all native speakers. In Arabic, however, when studying in depth, you usually have to choose whether to learn a specific dialect (e.g. Egyptian for communication) or the literary language for reading and formal speech, and ideally, gradually master both. Thus, Arabic is much more variable, while Hebrew is monolithic.

Arabic and Hebrew differ greatly in terms of the number of speakers and geographical distribution.

Arabic is one of the most widely spoken languages in the world (it ranks among the top five in terms of number of speakers). It is spoken by over 300 million people in more than 20 countries in the Middle East and North Africa. In addition, it has the status of an official language of international organisations and the sacred language of Islam throughout the world.

Modern Hebrew, although successfully revived, remains the language of a relatively small nation. It is spoken by about 9 million people, mainly in Israel (Hebrew is the official language of that country) and in Jewish communities in the diaspora.

The area where Hebrew is spoken (Israel) is marked in purple, and the area where Arabic is spoken is marked in green

In terms of distribution, these are incomparable quantities: knowledge of Arabic opens up communication with hundreds of millions of people, while Hebrew is the key to communication mainly within Israel and with Israelis. On the other hand, the relatively small community and concentration of Hebrew make it easier to maintain a uniform standard of the language and create a comfortable learning environment for it (for example, through specialised applications and interest clubs).

To sum up, we can say that Arabic and Hebrew are like cousins: sharing common linguistic and cultural «genes», they have grown up differently. Yes, historically and lexically they are closely related, but in practice there is no mutual understanding between them without special study. For language enthusiasts, knowledge of one of these Semitic languages can only facilitate familiarity with the other to a very small extent — through an understanding of the principles of roots and some similar words. Otherwise, they are two separate linguistic universes.