Israeli citizenship by roots (repatriates)

The most direct and simple path is repatriation under the Law of Return. The most direct and simple path is repatriation under the Law of Return. This is sometimes popularly referred to as Jewish citizenship, as it is intended for individuals of Jewish descent and their family members. According to this law, every Jew who wishes to return to their historical homeland has the right to Israeli citizenship.

In Israeli law, a Jew is defined as someone born to a Jewish mother or someone who has undergone a giur (official conversion to Judaism). In addition to Jews themselves, close relatives of a Jew – their spouse, children, grandchildren, as well as their children's spouses and grandchildren's spouses are eligible for an Israeli passport under a simplified procedure. This means that even if one of your grandparents was Jewish, you and your family (including your spouse) are eligible to immigrate.

It's important to note: if you were born Jewish but subsequently officially converted to another religion, you won't be able to exercise your right to repatriation. The law excludes those who voluntarily converted from Judaism to another faith. In all other cases, if you have Jewish roots, the path to Israeli citizenship is open.

Chances: Very high for those who actually have a Jewish ancestor and the necessary documents.

Israeli citizenship by marriage

Another option is to marry an Israeli citizen. Marriage to an Israeli opens the door to a passport for a foreigner, although not immediately. Israeli law recognizes family reunification, but the naturalization process through marriage is gradual and strict, to weed out sham unions. This path is not suitable for everyone, as it requires a real relationship and several years of waiting.

Terms: at least 5–6 years.

Chances: are high if the relationship is genuine and the paperwork is in order.

Note: Official marriage does not require foreigners to know Hebrew or renounce their native citizenship. This means that a Russian citizen who marries an Israeli citizen can retain their Russian passport. However, if the couple chooses a partnership instead of marriage, these benefits do not apply – they will have to prove their knowledge of the language and, possibly, renounce their previous citizenship. These nuances should be taken into account when planning immigration.

Israeli citizenship by naturalisation (without roots)

The most difficult way is to obtain Israeli citizenship without Jewish roots, not through marriage, i.e. through standard naturalisation. Israel does not have a migration programme for everyone (such as immigration to Canada or Australia based on points). Therefore, there is no easy way to arrive ‘from nowhere’ and become a citizen after a few years.

The law provides for naturalisation for foreigners, but imposes strict conditions for obtaining citizenship in this case:

- You must have lived in Israel legally for at least 3 of the last 5 years. In other words, you must already have a long-term residence permit in the country.

- You must have permanent resident status at the time of applying for citizenship.

- You must have at least a basic knowledge of Hebrew in order to integrate into society.

- You must reside permanently in Israel and intend to remain there (proof of ‘centre of vital interests’ – work, housing, family in the country).

- You must officially renounce your existing citizenship upon obtaining Israeli citizenship. This point often raises questions – the state as a whole allows dual citizenship, but the 1952 Citizenship Law gives the Ministry of the Interior the right to require naturalised citizens to renounce their previous citizenship. In practice, this requirement is waived for repatriates and spouses, but ‘ordinary’ naturalised citizens may be asked to renounce their previous citizenship.

Deadlines: 6–8 years before obtaining a passport.

Chances: It's difficult, but possible.

In conclusion, naturalisation is a realistic but very rare scenario. If you have no Jewish roots and no close relatives who are Israeli citizens, but you want to move there, first consider the alternatives: studying, working, or possibly converting to Judaism (giyur), which is discussed below. Naturalisation usually happens ‘by itself’ — you have lived in the country for many years on other grounds and have decided to legalise your status with citizenship.

Israeli citizenship by descent

Here we will discuss cases where the right to a passport is granted solely on the basis of having close relatives who are Israeli citizens. Some of these situations overlap with those already described, but there are also special categories.

- Born of an Israelite (by descent). If your father or mother had Israeli citizenship at the time of your birth, you are automatically considered an Israeli citizen by right of blood. Citizenship is passed on to children even if they were born outside of Israel. In this case, no separate procedure for ‘obtaining’ citizenship is required—it is sufficient to contact the embassy and register the fact of birth. Important: if the Israeli parent is the father and the marriage to the mother is not registered, a paternity procedure may be required before the child is recognised as a citizen. However, in general, the law protects the right of Israeli children to citizenship as much as possible.

- Repatriated children. When a family repatriates to Israel, the applicant's children (minors) automatically receive citizenship along with their parent, even if the child itself is not of Jewish descent. For example, a Jewish grandmother applies for aliyah and takes her granddaughter, who was born to non-Jewish parents, with her – the granddaughter will also become a citizen as a member of the repatriate's family. The same applies to adopted children.

- Reunification with children who are citizens. Conversely, the parent-child relationship can also facilitate emigration. The state allows single elderly parents of Israeli citizens to move to their children. If an elderly parent (usually over 65) has all their children living in Israel, they are entitled to permanent resident status under the family reunification programme. An important condition is that the parent must not have any other children abroad (to ensure that there is someone to support them in their home country).

- Widows/widowers and other family members. A special case applies if your spouse was Jewish and eligible for repatriation but has passed away; you still retain your right to citizenship under the Law of Return. The law applies to spouses of Jews even after their death, provided that the marriage existed before the death. Similarly, if your son or daughter were Israeli citizens and died, the parents or surviving spouse may obtain status on the basis of family ties – each case is considered individually.

- Other relatives. Having more distant relatives – a brother, sister, uncle/aunt, or grandchildren of a citizen – does not automatically grant you the right to immigrate. For example, if you have a brother who is an Israeli citizen, he cannot simply ‘invite’ you to become a permanent resident. At most, you can come on a work or student visa, and your brother can help you settle in, but there are no legal privileges for brothers/sisters.

- Chances: It varies. If you are the child of an Israeli citizen, you are a citizen by birth. If one of your parents is a citizen, you have a chance to become a citizen yourself in a couple of years. More distant relatives do not give you a direct legal right, but they can help indirectly.

Israeli citizenship by birth

Israeli law does not provide for automatic citizenship by birthplace – that is, the mere fact of being born on Israeli soil does not make a child a citizen unless at least one parent is a citizen. This is important for migrants from countries where the principle of jus soli applies to understand. In Israel, things are different: the principle of jus sanguinis applies.

If a child is born in Israel to foreign nationals, he or she inherits the citizenship of the parents, but not Israeli citizenship. However, the law protects such children from statelessness. A child born in Israel who does not have any other citizenship is entitled to apply for Israeli citizenship between the ages of 18 and 21, provided they have been a permanent resident of the country during those years.

If a child is born abroad to Israeli citizens, as already mentioned, he or she is an Israeli citizen by birth. However, in order to exercise this right, parents must apply to the consulate in a timely manner. In the first years of life, an application for birth registration must be submitted. The child will then be issued with a certificate of citizenship and a passport.

It should be noted that if Israelis adopt a foreign child, either in Israel or abroad, the child immediately receives citizenship (which is a huge advantage, as there is no need to wait, as in some countries). If foreigners suddenly adopt an Israeli child (which is an extremely rare scenario), the child will retain Israeli citizenship until they reach the age of 18 and renounce it themselves.

Israeli citizenship through giyur (conversion to Judaism)

Giur is a religious process of conversion to Judaism. In the context of citizenship, it is interesting in that a person who was not born Jewish acquires the right to repatriation after giur. Israel equates those who have undergone giyur with Jews by blood. Thus, for some people, giyur becomes a kind of ‘ticket’. But it is not that simple: giyur is a lengthy and complex religious act that requires sincere faith and the intention to observe Jewish commandments.

Duration: usually 1–2 years.

Chances: If the conversion is genuine and recognised, the right to citizenship is guaranteed by law. Refusal is only possible in special cases (for example, if it is discovered that immediately after conversion, the person continues to practise another religion – there have been such cases).

Other methods

In addition to those listed above, other options for obtaining Israeli citizenship are sometimes mentioned. We will briefly explain whether it is possible or impossible to become an Israeli citizen in the following situations:

- Adoption. A child adopted by Israeli citizens automatically becomes a citizen. However, adults cannot ‘sneak in’ through fictitious adoption, as Israeli law does not recognise the adoption of adults. Therefore, only children can acquire citizenship through their adoptive parents.

- Long-term stay. Simply staying in the country for a long time does not lead to citizenship. If you have lived in Israel for 10 years, but as a tourist or worker without permanent residence, then after 10 years you are still not a citizen. You must have an official residence permit and go through the naturalisation process. Even law-abiding foreigners sometimes live in Israel for years without citizenship.

- Services to the state. In exceptional cases, the government has the right to grant citizenship for special merits. For example, to a well-known person who has contributed to the development of the country, or to a descendant of the righteous people of the world. But these are isolated cases, and one should not count on them.

- Highly qualified specialists. Although the country is interested in attracting talented individuals (doctors, IT specialists, scientists), citizenship is not granted to such specialists immediately. They are given preferential treatment in obtaining work visas, which can be extended longer than usual, but they still have to wait for a passport through the standard procedure.

- Investments in the economy. Unlike a number of other countries, Israel does not sell its citizenship for investment. There is no ‘golden passport’ programme, where you can simply invest a certain amount in real estate or government bonds to obtain a passport. You can buy real estate, but this will not grant you a visa or citizenship on its own.

- Work and business. There is a special visa for Olim entrepreneurs (new immigrants) – Jews who want to start a business in Israel are eligible for benefits. However, there is no separate ‘business immigration’ for non-Jews. Obtain a regular business visa or work through an employer, and then follow the general procedure.

- Studying. Studying at an Israeli university or ulpan (language school) does not lead to citizenship. A student visa is issued for the duration of your studies and must be extended or changed to another status upon completion. Some, however, use their studies as an opportunity to gain a foothold: to learn the language, meet a future employer or spouse – that is, as a springboard to other grounds.

- Refugees. Israel takes a rather strict approach to asylum. Despite the fact that there are several tens of thousands of asylum seekers in the country (from Africa and the Middle East), only a handful have been granted full asylum and subsequent citizenship throughout history. Therefore, it is not worth counting on obtaining citizenship through asylum.

What Israeli citizenship offers

Once you obtain an Israeli passport, you gain a whole range of rights, freedoms and opportunities – in fact, you become a full participant in the life of a dynamically developing country:

- Israeli passport (darkon). The main attribute of a citizen is an Israeli passport, which opens doors to more than 150 countries around the world without a visa or with simplified entry.

- Right to permanent residence. As a citizen, you can live in Israel indefinitely; no one has the right to expel you or restrict your stay.

- Healthcare and social security. Citizens are entitled to state health insurance – for a small monthly contribution, they receive virtually free basic medical care. In addition to healthcare, citizens enjoy a full package of social guarantees. The state takes you under its wing, and you will not be left without support in difficult life situations.

- Education. Children who are citizens of Israel are entitled to free school education. After school, citizens can enrol in Israeli universities and colleges. Higher education is fee-based, but relatively inexpensive by global standards, and its quality is high (the Technion and the Hebrew University are consistently ranked among the top 100 universities in the world).

- Economic opportunities and taxes. Many professions that are closed to foreigners are open to you, such as civil service, defence enterprises, and certain areas of medicine. It is easier for citizens to start a business from a legal point of view. Regarding taxes: Israel is building a taxation system based on residency rather than citizenship.

- Military duty. This is a specific point that some consider to be a positive aspect of citizenship, while others consider it to be a negative one. Israel is a country with universal conscription.

- Housing. Israeli citizens have the right to freely purchase real estate and land (with rare exceptions for strategic land) in their own name. Foreigners are also allowed to buy property, but citizens are entitled to certain benefits.

- Political rights. Once you become a citizen, you gain the right to vote. You can vote in elections at all levels, from mayoral elections to parliamentary elections (the Knesset).

Darkon - Israeli foreign passport

Of course, citizenship also imposes obligations – to serve in the army, obey the law, pay taxes, and notify the Russian authorities of any second citizenship (otherwise, you face a fine of up to 200,000 roubles or forced labour under Russian law). However, for most people, the advantages significantly outweigh the disadvantages.

What is required for Israeli citizenship – list of documents

Once you have decided on the basis, you need to gather a set of documents. The details will vary depending on the basis, but there is a general list of documents that is required in almost all cases:

- Your country's foreign passport. It must be valid, and it is desirable that its validity period cover the next few years (at least 1–2 years), as the process may take some time.

- Internal passport (for citizens of the Russian Federation) or similar identity document – to confirm place of registration, marital status, etc.

- Birth certificate. Each applicant must provide an original birth certificate. This document is important for establishing family ties, especially in cases of repatriation or family cases.

- Documents regarding marital status. If you are married, you will need a marriage certificate. If you have been divorced, you will need divorce certificates. In addition, if your spouse has died, you will need a death certificate. These documents are required for both repatriation (to confirm family ties) and immigration through marriage (to confirm the marriage itself).

- Photos for documents. Typically, 2–4 colour passport-size photos (3.5×4.5 cm) are required. You will be informed of the exact requirements, but it is better to have a few extra photos on hand.

- Questionnaires and forms. The consulate or Ministry of Internal Affairs will provide application forms to be completed. These usually include an application for aliyah or visa support, a CV, a list of relatives, etc. They should be completed in Hebrew or English (staff will assist).

- Certificate of no criminal record. This document is not always requested, but often the consulate requires a certificate from the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation confirming no criminal record (especially for able-bodied men). It must be obtained in advance, as it takes about a month to process. The certificate must be apostilled and translated.

- Medical documents. As a rule, Israel does not require an official medical examination, as is the case when migrating to some countries. However, you may be asked to provide a doctor's certificate of general health or a vaccination certificate, especially if you have children. Repatriates are advised to get certain vaccinations upon arrival, but this is not a condition of entry.

- Military service record book (for men of conscription age from countries with compulsory military service). Israel is interested in your military status, especially if you are a repatriate of the appropriate age for the army. It is best to bring your Russian military service record book or registration certificate with you, just in case.

All foreign documents must be translated into Hebrew (or English, as specified by the consulate) and notarised. Many require an apostille. For example, birth certificates, marriage certificates, and other documents must be apostilled at the registry office or the Ministry of Internal Affairs, otherwise Israel will not accept them. The Israeli consulate in Moscow can certify copies of documents, but usually prefers an apostille.

Additional documents

Now let's list the additional documents for each specific reason beyond the general list.

For repatriation (aliyah based on Jewish roots). The key is proof of Jewishness.

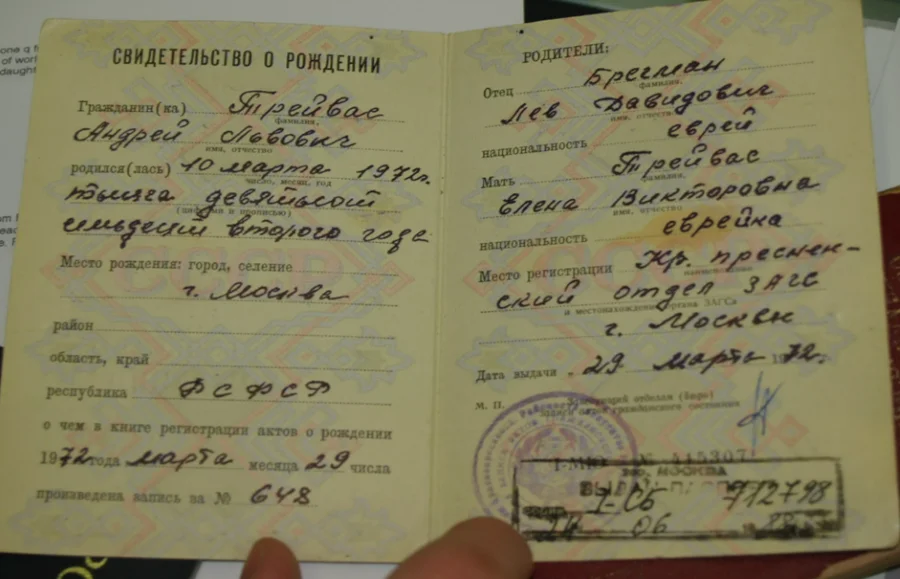

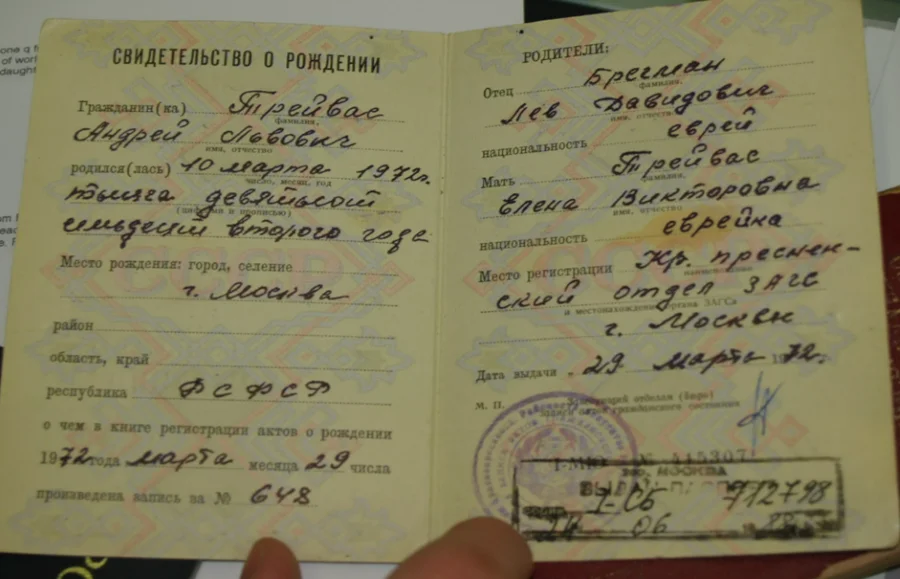

- Ancestral documents: birth certificates, marriage certificates of your parents indicating their nationality as ‘Jewish’; certificates issued by the synagogue; archival references to nationality from Soviet archives; old USSR passports with the fifth column; death certificates indicating nationality; ancestors' military ID cards, employment records indicating nationality, and any papers that can confirm your kinship with a Jew.

- Documents regarding the repatriation of relatives (if your parents/grandparents or other relatives have already obtained Israeli citizenship, you will need a confirmation letter from the Israeli Ministry of the Interior or a copy of their Teudat Olam).

- Family photographs, letters mentioning your Jewish heritage, newspaper clippings, and other items that will support your story.

- If you have undergone giyur, you must present your giyur certificate and a letter from the rabbi who conducted the process.

- Spouses and children of repatriates need documents confirming their relationship with the main applicant (marriage certificate, birth certificates of children).

- The consul may ask you to draw up a family tree listing all known Jewish relatives.

Example of a birth certificate indicating the nationalities of the father and mother as “Jewish”.

For marriage to an Israeli citizen. I need a complete set of documents for my spouse:

- The Israeli spouse provides an Israeli teudat-zehut (internal identity card) and a foreign passport.

- If the marriage was registered outside Israel, the marriage certificate must be legalised – apostilled and translated into Hebrew, and then registered with the Israeli Ministry of the Interior.

- Joint evidence of cohabitation: certificate of change of surname (if the wife has taken her husband's surname), joint registration or rental agreement for two people, bills in both names, family photographs (from when they met to the wedding), correspondence, testimonials from acquaintances (sometimes letters from friends/relatives are requested to confirm that the marriage is not fictitious).

- The Israeli spouse writes a financial support commitment, stating that he or she will take responsibility for the foreign spouse until the latter obtains status.

- Foreign spouses are often required to provide a certificate of no criminal record from all countries where they have resided, as well as a medical certificate (to rule out dangerous infections).

- In the case of marriage, it is particularly important to fill out the marriage verification questionnaire correctly, which asks questions about your biography, your relationship with your spouse, your language of communication, etc. Inconsistencies in the spouses' answers may alert the migration service, so the documents must be honest and detailed.

For naturalisation (without roots). Key document – confirmation of your permanent resident status:

- teudat-Zeut marked ‘green’ (non-resident identity card with permanent residence) or a separate permanent residence permit;

- provide an entry stamp or visa proving that you have lived in the country for the last few years;

- proof of registered address;

- bank statements for the last 3 years;

- document confirming your level of Hebrew proficiency – usually an ulpan (language course) certificate or YALPAN test results, or an interview with an official who will assess your level;

- a statement of willingness to renounce your current citizenship;

- proof of income and employment: employment contract, business certificate, tax returns;

- letters of recommendation – for example, from your employer, neighbours, local rabbi or municipality, who can confirm your good behaviour and integration into the community.

Permanent identity card Teudat Zeut (plastic ID card)

For citizenship by descent.

- If the basis is a parent who is an Israeli citizen, The main document is a birth certificate proving your relationship and your parent's passport/teudat-zehut. Your parent must file a request with the Israeli Ministry of the Interior, so they will need to provide a statement and a letter of guarantee.

- If the basis is a child who is an Israeli citizen (reunification of parents), you will need to provide birth certificates for your Israeli children, prove that you have no other children abroad (family composition declaration), and documents confirming your age and dependence on your children (e.g., pension certificate, if available). The widow of an Israeli citizen will need documents confirming her marriage and the death of her spouse, as well as confirmation that she has not remarried.

For citizenship by birth on the territory:

- birth certificate;

- proof that you do not have any other citizenship;

- proof of permanent residence in Israel (school certificates, statements of attendance at educational institutions, statements from neighbours, etc.);

- application submitted within the required age range (18–21 years old).

For the giyur. The more detailed the package about your hyure, the better for the consulate.

- Certificate of conversion (gerut) – official certificate issued by a rabbinical court;

- Letter from the head of the community that conducted the conversion, confirming your commitment to Judaism and participation in the life of the community;

- Mikvah certificate (confirming that you have undergone the ritual immersion), if issued;

- Documents confirming your membership in the community: for example, a certificate confirming that you are a member of the synagogue and attended classes from such-and-such a date to such-and-such a date.

Other cases: for investors – business plan, investment certificates; for specialists – educational diplomas, recommendations, letters from employers; for refugees – documents confirming persecution (UN decisions, political asylum certificates).

Important: All documents in Russian (or any other language) must be translated into Hebrew. The translation must be certified by a notary in Israel or by the consular department. Apostilles: Russian civil registry documents, certificates from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and criminal records must be apostilled. Without an apostille, they will not be considered valid.

How to obtain Israeli citizenship – step-by-step instructions

Below is a step-by-step guide, starting with preparation and ending with obtaining the coveted passport. These steps are summarised for different situations – the specific details will vary slightly for repatriates, spouses and naturalised citizens, but the general outline is similar.

Step 1. Assess your grounds and options

First of all, soberly determine which path you will take. If you have Jewish roots, your path is aliyah. If you have a fiancé/fiancée from Israel, your path is marriage. If you have neither, but you have the desire, perhaps you should consider giyur or employment. Your entire future strategy depends on this choice.

At this stage, it is advisable to consult with knowledgeable people or a solicitor so as not to miss any hidden opportunities. For example, find out about your family tree: suddenly, miraculously, your great-grandmother was Jewish, and the easiest path will open up for you.

Step 2. Gathering documents

Prepare the package described in the previous section. This is the most time-consuming part: searching for archival references, translations, apostilles, photos, filling out forms. Take this seriously, as the success of your interview depends on the completeness of your documents.

If you cannot find something, try to obtain replacement certificates – archive extracts, written statements from relatives. It is better to be safe and have an ‘extra’ document than to be rejected later because of its absence.

Step 3. Application submission and initial contact

Depending on the reason, you should contact either the Israeli consulate in your country or the Israeli Ministry of the Interior directly if you are already in Israel.

- Repatriates and candidates for aliyah submit their documents through the consular section of the embassy or through special representative offices of Nativ (an organisation involved in repatriation from former Soviet countries). In Moscow, this is usually the repatriation department of the embassy.

- Spouses of Israeli citizens: if the marriage is registered and you are both in Russia, start by contacting the Israeli Embassy, the department for working with citizens (they will tell you the visa procedure for entry). If the foreign spouse is already in Israel on a visa, the Israeli spouse should go to the local Ministry of Internal Affairs office and submit an application to start the ‘step-by-step process’.

- Naturalisation: the application is submitted within Israel, at the Ministry of the Interior department in the place of residence.

- Reunification with parents/children: either in Israel or through the consulate – this is handled on a case-by-case basis. Often, the Israeli citizen first applies to the Ministry of the Interior, and only then is the parent granted a visa.

- Giur: the process consists of two stages – the religious giur itself (unofficial, without state involvement), and then, with the certificate obtained, standard repatriation through the consulate.

Step 4. Interview and checks

In almost all cases (except for children by origin), you will be communicating with Israeli representatives:

- Consular verification of repatriates: an interview with the consul or a representative of Nativ. You will be asked about your origins and asked to tell your family history. If something is missing, they may give you a list of additions and invite you back. They may also talk separately with different family members to check that everyone is aware of the information. The aim is to confirm your right to aliyah.

- Interview on marriage: spouses may be interviewed together or separately. Questions range from ‘How did you meet?’ to ‘What colour is your husband's toothbrush?’ The aim is to ensure that the marriage is not fictitious.

- Interview when applying for naturalisation: An Interior Ministry official will test your knowledge of Hebrew, ask if you feel comfortable here, and whether you want to renounce your previous citizenship. You will also be asked to bring receipts and proof of residence – this is also a kind of check to confirm that you actually live here and are not just formally registered.

- Safety (shabak): In some cases, the case is sent to the security services for review.

- Medical examination: Repatriates do not undergo a medical examination at the consulate stage. However, once in Israel, if you are of conscription age, you will be examined by the military registration and enlistment office to determine your fitness category (for the army). For marriage and other visas, you may be asked to undergo fluorography (for tuberculosis) or provide a certificate confirming that you do not have any dangerous diseases.

Step 5. Receiving the decision and entry visa

After successfully passing the interview and checks, you will receive a decision.

Repatriates are issued with an ‘ole’ type immigration visa in their foreign passport – this is a single-entry visa for permanent residence. It is usually accompanied by a ‘repatriate certificate’ – a document that you must present upon entry.

The spouse of a foreigner is issued a B/1 (work/guest) entry visa or an A/5 visa, depending on where they are located.

Other categories are issued the appropriate visas: work, tourist for entry, or nothing if the person is already inside the country.

If the application is rejected, this is usually communicated in writing with justification. In case of rejection, additional documents can be collected and resubmitted, or an appeal procedure can be initiated.

Step 6. Moving to Israel

With a visa in your passport, you travel directly to Israel. For repatriates, the move is often organised by the Jewish Agency. Upon arrival at Ben Gurion Airport, new repatriates go through a special counter for new citizens: there you will be welcomed, given a teudat ole (repatriate certificate) and, as a rule, immediately a teudat zeut – an Israeli internal passport (if it is technically possible to issue it at the airport, which is now done quickly). They will also arrange medical insurance, may issue a SIM card from a local operator, and even make the first cash payment from the ‘absorption basket.’ From that moment on, you are a citizen of Israel. If you do not receive your teudat zehut at the airport, you will need to do so at the nearest Ministry of Internal Affairs office in your place of residence.

For spouses and other categories who do not obtain citizenship immediately, moving means the start of the residence countdown. A spouse with a visa enters the country, goes with their husband/wife to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, where they are given an A/5 stamp – temporary resident for one year. If the naturalised person was already living in the country at the time of application, they do not go anywhere, they are already in the country – they simply continue to live there.

Step 7. Fulfilling the necessary conditions after arrival

Depending on your category, there may be additional expectations:

- Repatriates do not need to do anything else upon arrival – they already have citizenship from the moment they enter the country. They only need to complete the paperwork (ID, bank account, register with a clinic).

- Spouses of foreign citizens must appear annually at the Ministry of Internal Affairs for an interview and to renew their A/5 visa. This is a 4-year probationary period. During this time, it is best not to leave the country for long periods, to maintain a joint household, and to keep documents (bills, photos) confirming your life together – all of this will be useful for subsequent interviews.

- Naturalised citizens (without roots) must live in the country for the required period of time after obtaining permanent residence, without leaving the country for long periods. It is advisable to be in the country for more than 75% of the time, otherwise there may be questions about the ‘centre of life’.

- New converts to Judaism are similar to ordinary repatriates – citizens from day one.

Step 8. Submit a request (if not received automatically)

For repatriates and children of citizens, this step is skipped – they are already citizens. However, spouses and others must apply for naturalisation after the specified period has expired.

After ~4 years of A/5, spouses are granted permanent residence and can immediately apply for citizenship (in fact, this happens simultaneously). They need to fill out the forms again, bring fresh certificates of family composition, income, and language proficiency (spouses are often not required to take an exam, but they will be tested). If the couple has had children in the last 4-5 years, they are also included. After submitting the application, there is one final interview, where they will ask some final questions and issue a referral for the oath.

For naturalised foreigners, the procedure is similar: once you have reached the required 3 years of permanent residence, you go to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and apply for citizenship. It is important to note that you must fulfil the obligation to renounce your foreign citizenship. You will be asked to provide proof that you have lost your previous citizenship. However, Israel may allow dual citizenship upon request. In the case of Russia, in practice, if you are a repatriate or spouse, you are not forced to renounce your citizenship, but if you are a pure naturalised citizen, in theory, you should be required to do so. This is decided on an individual basis. Nevertheless, the law is the law — be prepared for such a turn of events.

Step 9. Acceptance of citizenship – oath and certificate

The final step is the official registration of your citizenship.

The Ministry of the Interior will set a date for you to appear and take the oath of allegiance to the State of Israel. This is not a grand ceremony, as in the United States, but rather a formality: you read (or sign) the text of the oath to be a loyal citizen. This usually takes place in the presence of an official, sometimes collectively with other applicants.

After that, you are given a teudat ole hadrasha, i.e. a certificate of citizenship (for repatriates, this was at the airport, and for naturalised citizens, it is now). From now on, you are a full-fledged Israeli citizen! You will be assigned a personal number (tada-zeut), if you did not have one before. However, if you had permanent residence before, the number remains the same, only the status changes.

Step 10. Obtaining an Israeli foreign passport (darcon)

The final practical step is to apply for a foreign passport. With your new citizen ID card, go to the Ministry of Internal Affairs or Ministry of Foreign Affairs office that issues passports and submit your application. You will need photos and to pay the state fee (about 400 shekels for urgent service or 265 shekels for standard service). Within a few days or weeks, your biometric passport will be ready. As mentioned, new repatriates receive either a temporary laissez-passer or a passport with a shortened validity period for the first year. But ultimately, you will have a 5- or 10-year blue passport with the coat of arms. Now you can travel the world as an Israeli citizen.

This completes the registration process. If you have successfully completed all the stages, you will have received all the necessary documents: an Israeli internal passport (ID card), a foreign passport, and you will be registered in the healthcare system and the voter registry. You are a citizen of the country. You can celebrate your new home in the Promised Land!

Process duration: let's summarise approximately how long the registration takes:

- Repatriation: usually 4–12 months.

- Marriage: 5–6 years.

- Naturalisation: if you are already in Israel for work, expect at least 5 years. If you are still outside the country, add the time it takes to obtain a work visa and residence before permanent residence, which can add up to 10 years in total.

- Giur: ~2 years.

- Parents of citizens: ~3 years.

- Children of citizens: processing documents takes 1–3 months.

How much does it cost to obtain Israeli citizenship in terms of official fees?

The state does not charge high fees. For example, repatriation is exempt from administrative fees altogether. Naturalised citizens pay a symbolic state fee of about $50 (USD) for submitting an application, plus approximately the same amount for each stage of the residence permit/permanent residence permit process. Foreign spouses pay a one-time fee of approximately $278 when applying for a residence permit. Subsequent renewals are often free or subject to a minimal fee. The main expenses are translations, apostilles, and travel. If you hire a solicitor or firm, the cost can reach several thousand dollars for their services. But if you do everything yourself, the direct costs are not high: certificates, apostille (about 2,500 roubles per document in the Russian Federation), translation (500-1,500 roubles per page), medical examination (if necessary), and plane tickets. Thus, officially obtaining citizenship is inexpensive — you spend much more time and effort than money.

Refusal of Jewish citizenship – possible reasons

Unfortunately, the process does not always go smoothly. There are cases when the authorities make a negative decision.

Possible reasons for refusal:

- Insufficient evidence of Jewish ancestry. The most common reason for rejecting a repatriate is that the consulate considers that the documents submitted do not prove your right to aliyah.

- Falsification of documents, false information. If fraud is discovered in your case, rejection is inevitable. This applies to repatriates, spouses, and others. Falsification of documents is not only grounds for rejection, but may also result in a ban on reapplication.

- Conversion to another religion (for aliyah). As already mentioned, if it turns out that you were born Jewish but were baptised into Christianity, converted to Islam, etc., repatriation is not possible. There is no point in denying it if it is a fact – they will check anyway (using baptism records or certificates). Therefore, in such a situation, refusal is usually immediate.

- Serious legal problems, security threats. Israel has the right to reject any candidate who poses a threat to society or state security.

- Sham marriage. For spouses who are citizens, the main reason for rejection is recognition of the union as a sham. If inspectors find that the couple does not actually live together, their answers in interviews do not match, neighbours confirm that ‘they do not live together,’ or correspondence is found that proves a purely commercial agreement, the visa will be denied and, accordingly, citizenship will be denied.

- Failure to comply with the conditions of naturalisation. A naturalised person may be refused if they have not met the requirements.

- Refusal on health grounds. Formally, the law does not contain any health requirements for repatriates or immigrants (the country humanely accepts even disabled and seriously ill people). However, in practice, there are known cases of refusal of elderly repatriates. Officially, this is not stated, but another reason will be found.

- Technical reasons. Sometimes, a refusal is issued due to bureaucratic issues: for example, your certificate has expired, you did not follow the correct procedure, or Israel suddenly suspended the acceptance of documents (rare, but it did happen during the COVID pandemic). These refusals are not final – once you have sorted out the formalities, you can reapply.

- Revocation of citizenship already obtained. This is rare, but it does happen. If fraud is discovered post factum. A naturalised citizen may also be stripped of their status if it is found that they have violated their oath – for example, by engaging in espionage against Israel. However, it is difficult to revoke the citizenship of repatriates by law, unless the person themselves renounces it.

What to do in case of refusal

First, figure out why it was rejected. You should receive a written notification with the reason. Sometimes it is very vague (‘insufficient grounds for recognising the right to repatriation’), sometimes specific (‘knowingly false information was provided’). Your strategy depends on this.

Option 1: Revise and resubmit. If the reason for the refusal can be remedied, the best course of action is to remedy it and try again. Sometimes it is worth changing the country of application — if one consul has refused, you can apply to another consulate (but they share information, so this does not always work). However, with additional documents, the same consul may reconsider the decision. Persistence is important here.

Option 2: Appeal through a solicitor. When you believe the refusal is unjustified (you have provided everything, but they still won't give you a visa), there is the option of hiring an Israeli solicitor and challenging the decision. For repatriates, this may be a complaint to the Israeli Ministry of the Interior or even a lawsuit demanding recognition of the right to aliyah.

For spouses, there is a procedure for appealing a visa refusal – usually an appeal is filed with the Ministry of the Interior or directly with the administrative court if the refusal is final.

Option 3: Take an alternative route. If one door has been closed to you, consider a workaround. For example, you have been denied repatriation because there is no evidence and nothing to dig up. Well, consider giyur.

Option 4: Postpone and try again later. If the reason for rejection is subjective and time may change it, wait. For example, if you were rejected because your marriage is ‘too young,’ live together for 2-3 years, build a life together, and then reapply.

Option 5: Contact an organisation for support. If rejected, it is useful for repatriates to contact Jewish organisations, such as Sohnot (the Jewish Agency) or the local Jewish community. They can issue recommendations, letters of confirmation, and sometimes even petition Nativ on someone's behalf. Such public support can sometimes help overcome bureaucracy, especially if you are indeed Jewish by origin but the bureaucracy has not recognised you as such.

Overall, rejection is unpleasant, but it is not the end of the world. Israel is known for its bureaucracy, but also for its people-centred approach: if you are persistent and right, you will ultimately achieve your goal.

Pros and cons of Israeli citizenship

Every citizenship has two sides – the rights and opportunities it provides, and the responsibilities and restrictions that come with it. Israeli citizenship is no exception.

Advantages:

- Second citizenship without renouncing the first. Israel allows dual citizenship. Repatriates and spouses from Russia can keep their Russian passport – the Israeli one will be their second.

- Freedom of movement. An Israeli passport provides visa-free or simplified entry to around 150 countries.

- High quality of life and social guarantees. Israel is a country with a developed economy, excellent healthcare and education.

- Strong community and support from the diaspora. Becoming an Israeli citizen means joining the global Jewish community. This includes culture, traditions and mutual support. Israelis are very united, especially in the face of external threats.

- No language barrier (for Russian-speaking repatriates). Israel has a large Russian-speaking community (repatriates from the USSR/CIS). According to estimates, about 17% of the population speaks Russian.

- Opportunity to participate in the governance of the country. For active people, citizenship comes with the right to vote and be elected. You can influence state policy and promote ideas that are important to you.

- Personal growth and career. Israel is a country of start-ups, with plenty of jobs in high-tech, medicine and science. It is easier for citizens to find high-paying jobs and gain access to certain vacancies.

- Security and democratic freedoms. Despite the difficult situation in the region, Israel provides a high level of personal security for its citizens (crime is low). It is a constitutional state: human rights and freedom of speech are respected, and there is no internet censorship.

- Family. Citizenship makes family life easier: you can pass on your status to your children without any red tape. Your future children will automatically be citizens, wherever they are born. You can reunite with your parents. Marriage between citizens is much simpler in terms of formalities than if one partner is a foreigner.

- Financial advantages. An Israeli bank account, credit history — all of this is open to citizens. It is easier to take out a loan or a mortgage (preferential rates for new repatriates).

- A sense of homeland. For those with Jewish roots, emotional satisfaction is important: it gives a sense of belonging to a people, pride.

Disadvantages:

- The need to notify the Russian authorities about second citizenship. According to Russian law, citizens must notify the Ministry of Internal Affairs within 60 days of obtaining foreign citizenship. This is a formality (the penalty for non-notification is up to 200,000 roubles), but it must not be forgotten.

- The risk of being drafted into the army. If you or your children are young, Israeli citizenship almost certainly means military service.

- The threat of terrorism and war. The downside of life here is periodic military conflicts and the threat of terrorism.

- High cost of living. Israel is one of the most expensive countries in the world. Housing prices, especially in the centre, are very high (Tel Aviv is in the top 10 most expensive cities in the world). Food and services are also not cheap.

- Climate and culture – not for everyone. The hot climate, the need to know Hebrew, and differences in mentality are disadvantages for some people. Summers are very hot, and air conditioning is not ideal everywhere. Hebrew is a difficult language, not everyone can learn it, and without it, career growth is limited. You can find out where to start learning Hebrew in our article.

- Restrictions on visiting certain countries. With an Israeli passport, you cannot officially enter a number of Muslim countries (Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Libya, etc.).

- No automatic transfer of citizenship by birthplace. If your child is born in Russia and you do not apply for Israeli citizenship by descent, Israel will still recognise them, but you will have to deal with the bureaucracy.

- Obligation to be loyal to the state. When you receive citizenship, you take an oath of allegiance. This means that you cannot participate in anti-state activities.

- Possible renunciation of previous citizenship upon naturalisation. This point applies to an extremely small number of people (non-Jews undergoing naturalisation). For them, the disadvantage is that the law requires them to renounce their previous citizenship.

Assistance in obtaining citizenship in Moscow

The process of gathering documents, communicating with the consulate, and completing other formalities is quite laborious. Not every applicant is confident that they can handle it on their own, especially if there is a language barrier or a complicated situation. Fortunately, there are many options, both official and private:

- Israeli Embassy and Consulate in Moscow. Located in Moscow (Bolshaya Ordynka, 56). It has a consular section that deals with repatriation issues, visas for family members, and documents. It also accepts documents for aliyah and conducts interviews.

- Israeli Cultural Centre (Nativ). Israel has cultural centres in Moscow and several other cities in the Russian Federation. They are run by the Nativ organisation. These centres hold seminars and Hebrew language courses, and most importantly, they conduct preliminary checks on eligibility for repatriation.

- Jewish Agency "Sokhnut". It is an international Jewish organisation that has been involved in repatriation for many years. In the Russian Federation, Sochnut is currently facing legal difficulties. However, Sochnut is still accessible online.

- Russian-Israeli public organisations. There are several organisations in Moscow that position themselves as cultural centres, repatriate clubs, etc. Some of them, with the support of the embassy, advise potential emigrants. These are semi-voluntary associations, often created by former repatriates who are temporarily residing in the Russian Federation. They can share their personal experiences of gathering documents, provide contacts for translators and notaries, and offer advice.

- Private firms and solicitors. The market for immigration services is large. In Moscow, many law firms offer turnkey solutions for obtaining Israeli citizenship.

Conclusion

Israeli citizenship opens up great opportunities – from personal security to new career prospects. For Russians, the easiest way is to exercise their right to repatriation based on Jewish ancestry. This is a state-guaranteed basis, although it requires effort in gathering documents. If you do not have Jewish ancestry, there are options for long-term residence (work, study, marriage) and subsequent naturalisation – a more complicated but realistic path. In any case, preparation plays a key role. It is necessary to find out the requirements in advance, brush up on the language and patiently go through all the stages. Then obtaining Israeli citizenship for Russians will become an achievable goal, allowing them to find a new homeland without losing touch with their former one.